How to be a Christian Entrepreneur

Here’s my “Startup” column from the June 2015 issue of Christian Computing magazine.

Over the past few months, I’ve introduced the concept of a “startup” and we’ve discussed why the church should really care about startups. We’ve developed this definition for our discussion: A startup is a new venture working to solve a problem where the solution is not obvious and success is not guaranteed. We learned that the Lean Startup methodology introduces the scientific method into the new venture process, with multiple hypothesis-test-observe-refine iterations, and we discussed how we can implement this in our ministries (and our businesses). This month, I want to talk about the person doing this – what does it mean to be a Christian Entrepreneur?

What is an Entrepreneur?

In my previous articles, I’ve used the phrase “startup” quite a bit and we even developed a good working definition that can be used whether starting a new venture in business or in ministry, but we haven’t used the word “entrepreneur.” What does that big word mean, and how does it apply to what we’ve been talking about?

According to Merriam-Webster.com, an entrepreneur is “a person who starts a business and is willing to risk loss in order to make money.” In other words, an entrepreneur is a person who starts a startup. Of course, the definition that Merriam-Webster uses works great if you’re starting a for-profit business, but just as we had to modify our definition of “startup” to encompass ministry startups as well as business ones, I think it’s worthwhile to do the same for “entrepreneur.” I propose that we broaden the definition to say “an entrepreneur is a person who starts a new venture and is willing to risk a loss in order to achieve the objective.”

What is a “Christian” entrepreneur?

Hopefully you can get a sense from that definition of an entrepreneur of how we might be “all in” when we’re pursuing the cause of Christ, but I think it’s helpful for us to explicitly think about what might be different about a Christian entrepreneur in contrast to an unbelieving entrepreneur, whether we’re involved in ministry or business.

Some would argue that the word Christian works much better as a noun than as an adjective, and I agree there’s some wisdom in that claim. If you’re in that camp, then I think it helps if we start by thinking about the term “Christian entrepreneur” as if there were a comma between the two words, so for example I might say: “I want to be a Christian, entrepreneur” – I want to be successful in my calling as a Christian and in my calling as an entrepreneur.

I’m going to look very briefly at what it means to be a Christian, and when I’m done, I’m hoping that you’ll see and believe that the comma we’ve temporarily inserted there can’t act like a brick wall separating how we act as a Christian from how we act as an entrepreneur. No, in reality, what the comma should be is more like a lens, applying what it means for us to be a Christian on what it means to be an entrepreneur. I say that now, even though you may not yet agree with me, so that as you read what follows, you’ll have in mind both what it means to be a Christian independent of anything else in our lives and how being a Christian might impact the way in which we act as an entrepreneur.

So, what does it mean to be a Christian? God has given us the Bible to answer that question. The entire book speaks to that topic, but especially the New Testament Epistles teach us how to live as redeemed believers in Christ living in a fallen world.

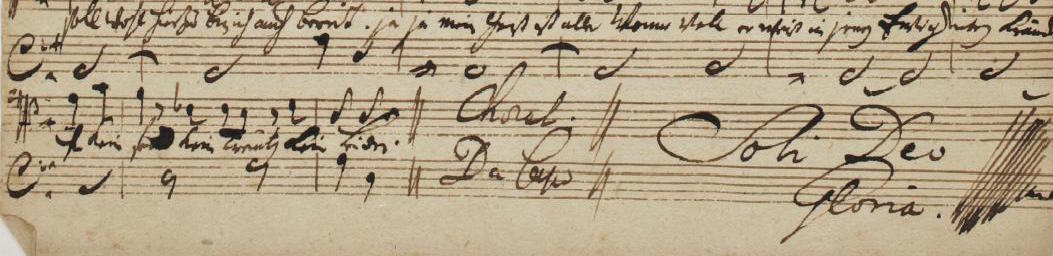

As a very simple example, I’d like to briefly look at three verses from Colossians: “And let the peace of God rule in your hearts, to which also you were called in one body; and be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom, teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord. And whatever you do in word or deed, do all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through Him” (Colossians 3:15-17).

I think a very simple summary of these three verses is that we are commanded to do three things.

First, we are commanded to “let the peace of God rule in your hearts” – in other words, the peace of God, which comes through the Prince of Peace, Jesus Christ, to those who believe in His name, is to rule in us. When the unruly passions (described earlier in Colossians 3) rise up in our lives, we are to put them off and put on the love of Christ, living our lives in a way that demonstrates the peace that we have through repentance and reconciliation with God. In other words, the way we live our lives should be different from how the lost around us live their lives, and I believe the way we operate our businesses will also be different.

Second, we are commanded to “let the word of Christ dwell in you richly” – in other words the Word of God is to live in us, as a master over our lives. We must spend time in the Bible and seek the wisdom of God from Biblical teaching, Godly counsel, and even being encouraged in the Biblical truths reflected in hymns and spiritual songs. Although this commandment comes second in the list, it is a prerequisite for the first commandment, as God’s Word informs us in how the peace of God should rule in our lives. As Christians, all of our decisions in life (and in our business) must be approached prayerfully and seeking the wisdom and will of God as revealed in His Word.

Third, we are to let the name of the Lord Jesus be glorified in all that we do. We must be thankful for God’s grace and blessings in our lives (and our businesses), acknowledging that He is the source of all good things, and desiring to please Him, to glorify Him, and to proclaim Him to the lost world around us. As a Christian, our driving motivation is different from the world’s. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to operate a profitable business, but we can’t let our desire for profits rule how we run our business. Instead, we must seek to glorify God in all that we do, including in operating our businesses with excellence.

With that as a foundation, I propose this definition: A Christian Entrepreneur is a person, driven to glorify God in all he does, and ruled by the Word of God, who starts a new venture and is willing to risk a loss in order to achieve the success of the venture.

How to be a Christian Entrepreneur Read More »