Just as Sundar Pichai did, I think it makes sense for us to look historically at Google’s forays into mobile and connectivity. I think there are three historical precedents to consider: Android, Nexus, and Google Fiber.

Android

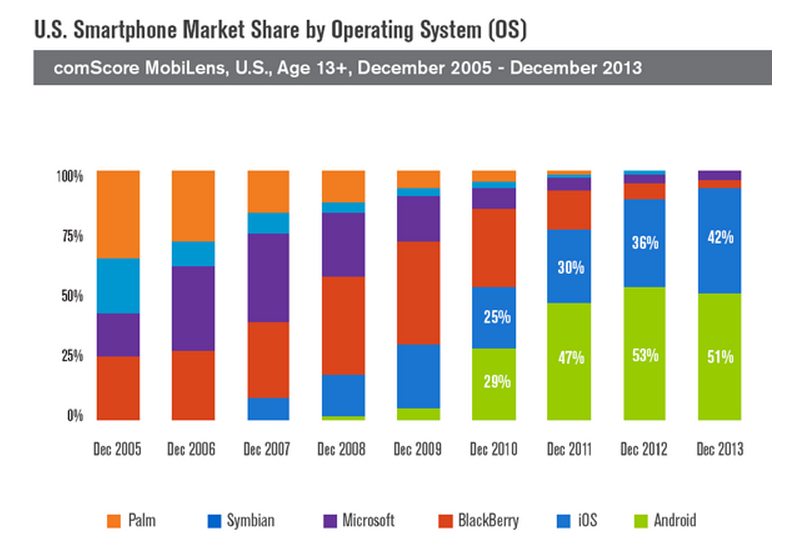

Google followed Apple into the smartphone market. You can either say that, together, they created the smartphone market, or you can say that they significantly disrupted an existing market dominated by RIM (Blackberry), Microsoft, Palm, and Nokia (Symbian). Google had virtually no meaningful relationships with any of those four, but Android was a key element in the destruction of what had been a very strong relationship with Apple.

Google followed Apple into the smartphone market. You can either say that, together, they created the smartphone market, or you can say that they significantly disrupted an existing market dominated by RIM (Blackberry), Microsoft, Palm, and Nokia (Symbian). Google had virtually no meaningful relationships with any of those four, but Android was a key element in the destruction of what had been a very strong relationship with Apple.

Including Apple, four of the five market leaders all had an integrated hardware/software approach to the market. Google chose an “open” or “ecosystem” model, similar to Microsoft’s successful approach to the PC market. In fact, the initial announcement of Android was made by the Open Handset Alliance, made up of 34 companies including OEMs, Operators, Developers, and Chipset companies.

Today, by far, Android is the dominant smartphone operating system. In his talk last week, Pichai claimed that 8 out of every 10 phones shipping around the world are running Android. Google has built a strong relationship with OEMs and, somewhat less directly, with Mobile Operators, to get Android to market. It is important to remember how critical Android was for Operators to have a competitive response to AT&T which had the exclusive on the iPhone. Verizon particularly rode the Droid horse hard until they gained access to the iPhone.

It is also important to note that Google’s Android play has always been focused on their core business model – increasing how much time each of us spends online, with Google providing web-based services and enabling monetization by 3rd party developers that ultimately drive advertising dollars for the company. (Advertising represented $59B of their $66B in 2014 revenues.)

Nexus

In January 2010, Google partnered with HTC to launch the Nexus One smartphone running the latest release of Android. The phone introduced some new features, but mostly it was an attempt by Google to demonstrate how strong a “pure Google” device could be. At least to some extent, it was an attempt to get the OEMs to stop modifying the Android platform. As you may recall, at the time, there was a fair amount of noise in the marketplace about fragmentation in Android (multiple operating system versions, different screen sizes, user interfaces, etc.) relative to the monolithic iPhone.

With the Nexus One, Google also tried to introduce a new approach to the market, selling an unlocked phone at full price, only available for purchase via a website, and with customer service only available via online support forums. None of these experiments were successful and undoubtedly contributed to the lack of success for the phone itself.

The second Nexus handset, the Nexus S (based on Samsung’s Galaxy S platform) was more successful. It introduced the Gingerbread version of Android (2.3) and had hardware specs that were impressive, including NFC. In fact, the Sprint version of the Nexus S became the launch device for Google Wallet. For this second Nexus device, Google stepped back from selling only on the web, selling as a full price unlocked device, and providing support through forums. Instead, they adopted the traditional industry models – sales and support primarily through the Mobile Operator channels.

Google has continued to partner with OEMs to introduce new Nexus phones, often using each new model as an opportunity to introduce new capabilities that perhaps the OEMs and Operators weren’t yet ready to place a bet on otherwise. It’s important to note that Google had to work hard to make sure that this program didn’t alienate the OEMs and Operators on whom the company was dependent. With each Nexus, Google partnered with a different OEM, and made sure that versions were available for the major operators.

To some extent, Google has used the Nexus devices to continue to push openness and capabilities that can enable mobile devices to be used for more and more applications, ultimately driving their core business.

Google Fiber

On February 10, 2010, Google announced plans to build an experimental fiber network, delivering 1GBPS, which they characterized as “100 times faster than what most Americans have access to today”. In their press release, they said “We’ve urged the FCC to look at new and creative ways to get there in its National Broadband Plan – and today we’re announcing an experiment of our own.”

As with Nexus, they made a big deal about the scale being not too small and not too big, saying that they would deliver the service to as few as 50,000 and as many as 500,000 people. They said their goal “is to experiment with new ways to help make Internet access better and faster for everyone” and they specifically called out enabling developers to come up with next generation apps, test new deployment techniques that they would share with the world, and provide openness and choice, managing the network in an open, non-discriminatory, transparent way and giving users a choice of multiple service providers.

They seemed (at least initially) to not want to offend existing broadband providers, saying “Network providers are making real progress to expand and improve high-speed Internet access, but there’s still more to be done. We don’t think we have all the answers – but through our trial, we hope to make a meaningful contribution to the shared goal of delivering faster and better Internet for everyone.”

With that initial announcement, they invited communities to express interest and more than 1000 did, with many doing crazy things to try to win the network for their community. I live in the Kansas City area (the winning city), and although Google Fiber is not yet available in my neighborhood, it has been a big catalyst for innovation across the metro area.

As has been well documented, Google’s entry into broadband also forced the existing broadband providers to improve their offers (speed, capabilities, and/or price). As Google Fiber has pushed into new neighborhoods and suburbs, the competitors have had to respond. Google is coming to my neighborhood this year and that has caused AT&T to expedite construction on their GigaPower infrastructure and for Time Warner to build out outdoor WiFi using streetlight mounted antennas. Everyone is offering special deals with multi-year commitments. We’ve seen similar competitive responses as Google has announced Fiber projects in additional cities.

Of course, Google Fiber is no longer a friendly, sub-scale experiment intended to help the broadband providers. In December 2012, Eric Schmidt said “It’s actually not an experiment; we’re actually running it as a business,” and he announced expansion to additional cities.

As with Google’s other telecom initiatives, the primary focus continues to be the core business. Google Fiber, both directly and indirectly, is driving more overall Internet use, and that helps drive Google’s services and advertising revenues. It’s also important to note that Google has traditionally not had a strong relationship with broadband providers, so they likely felt free to take a more disruptive approach to the market than with Android and Nexus.

In my next post, we’ll take this historical perspective, combined with Pichai’s comments, and combined with an understanding of the challenges that MVNOs traditionally face, and try to speculate on what a Google MVNO might actually look like.